The Maze of Science Communication

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the importance of clear and accessible science communication. Research indicates that during times of uncertainty, people turn to various media outlets for information. However, while trust in official channels seemed to be high during the start of the pandemic, it went on a decline as more and more time passed. Slowly but surely, fake news took over and started to feed doubts of parts of the general public. Additionally, since the pandemic was something new and science unfortunately is not a straight path to the “truth”, contradictory information worsened the ongoing infodemic. In times of social media fake news spreads faster and wider while fact checking is time intensive and usually can not keep up with everchanging cherry picking of information.

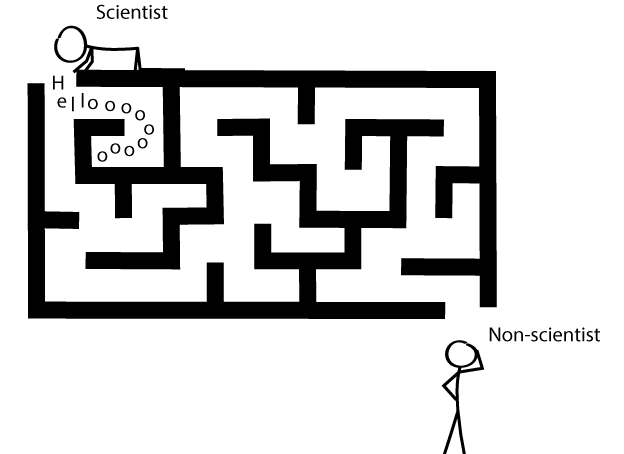

Effective science communication could combat this. But we are far away from being effective. Currently, science communication is a maze. Far away from being effective. Today it looks something like this:

The accessibility of scientific information remains a significant challenge for non-scientists, primarily due to barriers like paywalls. Imagine someone with a genuine curiosity about a scientific topic hitting a dead end because they can’t afford access to relevant journal articles. It’s frustrating and counterproductive. While there has been progress in promoting open access, with about half of scientific papers still hidden behind paywalls , we are far from achieving universal accessibility (1). Open access should be the norm, not the exception, empowering anyone with an interest in science to explore and learn.

With the advent of antibiotics, previously deadly diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and sepsis became treatable, saving countless lives in the process. And like this, antibiotics quickly became the cornerstone of modern medicine, transforming healthcare as we know it.

Peer-reviewed articles, though indispensable for scientific discourse, often present a daunting barrier for non-experts. The technical language, assumed pre-knowledge, and complex sentence structures can alienate even those with a genuine interest in learning. It’s not that scientists purposely exclude the public; rather, they’re often trained to communicate with their peers, not lay audiences. Bridging this gap requires a shift in mindset and approach. Scientists must learn to communicate effectively to specific target groups, employing language and formats that resonate with diverse audiences. In the end it is a massive difference if you want to communicate science to a fellow researcher, a 6 year old, or a 60 year old. It also doesn’t help that there’s little incentive or training for scientists to engage in public outreach. However, the benefits of effective science communication are immense, fostering understanding, trust, and engagement among the public.

And like this, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are just two of the nasty bacteria that are becoming increasingly common. Already today, they pose a significant threat to public health and already give us a little sneak peak into what a “post-antibiotic era” would look like — an era where common infections become untreatable, and even minor injuries could prove fatal.

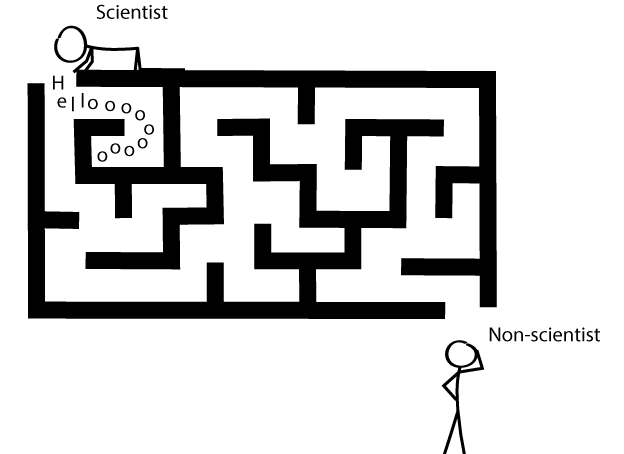

Better, but still not good enough to reach the broad public as intended. Let’s continue removing bricks.

Trust is the cornerstone of effective communication, influencing how we perceive and interpret information. In the realm of science, trust is crucial, yet it can be fragile. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated this, with public trust in science fluctuating amid rapidly evolving information and uncertainty (2). While trust is often associated with familiarity (think ads with familiar faces) and prior exposure (3), it’s also influenced by ideological beliefs (4) and communication practices. Scientists must acknowledge and address these factors to build and maintain trust. Transparency about the scientific process, including uncertainties and limitations, is essential for fostering trust. Moreover, normalizing the acceptance of uncertainty in science is crucial, as it reflects the dynamic and evolving nature of scientific inquiry. IT IS OK TO SAY “WE DON’T KNOW”!

We’re getting there.

In today’s digital age, social media platforms are where many people, especially younger generations, consume information. Yet, amid the deluge of content, distinguishing fact from fiction can be challenging. Real science often struggles to compete with sensationalized or misleading narratives. Harnessing the power of modern media channels is essential for effective science communication. However, creating engaging, informative content for these platforms requires expertise, time, and resources. Integrating science communicators into research projects can help bridge this gap, ensuring accurate and engaging content reaches broader audiences.

There is a long way to go for science communication. The COVID-19 pandemic showed that there is the urgent need for it but it also highlighted how bad science really is in communicating interesting topics in rather boring and complicated ways. The same is true for antibiotic-resistance. Even in western countries, many remain unfamiliar with the term “antibiotic-resistance” and its underlying concepts (5, 6). Astonishing, right? Especially considering the WHO is calling antibiotics one of the biggest global challenges of the 21st century… a “One-Health” phenomenon that requires the effort of every single person, but yet we fail to deliver the message to large parts of the human population at all.

Science needs to get better in communicating science. Not tomorrow — today! In the end, isn’t the aim of science to better the human condition? And shouldn’t humans understand it for this to happen?

References

(1) https://www.stm-assoc.org/oa-dashboard/uptake-of-open-access/#:~:text=When%20combined%20in%20our%20analysis,been%20published%20as%20gold%20OA

(2) https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/americans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/

(3) Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880.DOI: 10.1037/xge0000465

(4) Kai Shu, Amy Sliva, Suhang Wang, Jiliang Tang, and Huan Liu. 2017. Fake news detection on social media: A data

mining perspective. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newslett. 19, 1 (2017), 22–36

(5) https://www.who.int/news/item/16–11-2015-who-multi-country-survey-reveals-widespread-public-misunderstanding-about-antibiotic-resistance

(6) https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/file/b24978000_Exploring%20the%20consumer%20perspective.pdf